MCP Prompt Injection Attacks: How to Protect Your AI Agents

Last week, there were two near-invisible prompt injection attacks that slipped past the default enterprise guardrails. Last Wednesday, Varonis Threat Labs revealed a massive exploit where attackers could steal endless private information via Microsoft Copilot. Hours later, PromptArmor revealed how Claude Cowork can be manipulated to share sensitive information despite built-in prompt injection prevention.

Both of these attacks exploit trust. The AI trusts the user’s input, and the user unwittingly trusts a convincing Copilot phishing link or free resource to upload to Claude Code.

Both of these attacks were also foiled by Runlayer. Reprompt fails at the first phishing link. The Claude Cowork .docx exploit gets caught before the file upload. Here's how: Runlayer sits between users and AI systems. All inputs—even those trusted by users—aren’t trusted by Runlayer until they pass our security models that are continuously trained on the daily exploits.

Trusting built-in safeguards isn’t enough

In the past, stealing data relied on a mistake. Attackers might’ve exploited an open API gateway, dispatched a privileged script, or phished users with a deceptive OAuth link. However, these attacks were limited by nature: attackers could only access whatever was within the exploit’s domain. If an attacker gained entry to a list-documents endpoint, they could only extract document file names.

Now, attackers just need to dupe a user into including their natural language prompts. By hijacking the user’s privileged context, attackers can often access anything. A single mistake could escalate into an ongoing silent data leak.

Agent providers, like Microsoft and Anthropic, have responded to this with passable safeguards to scan for exfiltrated data or untrustworthy prompts. However, these safeguards have shortcomings. Previously, APIs could be secured by carefully defining the authorization boundary. Now, developers need to play a fuzzy war of words. Security measures are reduced to a “does this look right?” analysis that could be evaded by trial-and-error. It’s akin to how video game servers forbid profanity, but kids get clever with emojis or special characters to sneak past them. Universal security guardrails are going to be tricked.

Today’s attackers have one priority: evading this first barrier of guardrails. After that, they need to do the easy part: convincing at least one user to fall for a phishing link or legitimate-appearing file.

Last Week’s Attack 1: The infinite Microsoft Copilot exploit

Varonis Threat Labs demonstrated how attackers can bypass Copilot’s built-in mechanisms that would otherwise stop prompt injections. Dubbed Reprompt, this attack is dangerous. The user just needs to be fooled once into clicking a phishing link. It might appear legitimate, such as a link with an icon on an imitative website or email. After the user clicks the link, the attacker uses URL parameters and a chain of requests to continuously exfiltrate secret data.

Reprompt starts with a legitimate-appearing prompt. Only on further requests, which might happen after the user closes the tab, does the attacker’s server siphon sensitive data.

Given that users are easily phished, Reprompt turns a single mistake by any employee into a nonstop data leak. Even worse, this attack happens instantly. The user doesn’t stand a chance to stop it, even if they realize after-the-fact that the link wasn’t trustworthy. Soon, their company’s files, user’s data, and logged personal data are all stolen via recursive prompts dispatched by the attacker’s server.

This isn’t a hypothetical attack. Varonis demonstrated how this could happen to anyone today. Microsoft has since patched the exploit, but it’s only a matter of time before attackers find a way to sidestep the patch.

Last Week’s Attack 2: Fooling Claude Cowork with a .docx

PromptArmor showcased a similar exploit with Claude Cowork. Claude Cowork is a local agentic application that can do tasks on the user’s Desktop. Users will frequently give Claude Cowork access to their confidential local files, including business data (e.g. a Dropbox folder, a stash of financial statements etc). Additionally, users might often upload files that they found online to expedite their work. For example, a user might download a free NDA template or research paper. Today’s attackers are smart they could imitate these same resources.

Claude transforms any file upload into a flattened Markdown file. For example, a Microsoft Word file might appear legitimate when opened on Microsoft Word, but Claude will treat any text—including 1 pt font or invisible white text—as normal text. It’s a common technique known to pranksters and lazy students; now, attackers could use it to exfiltrate personal file data. By including their own Anthropic API key, attackers could then fool Claudex5 code execution to share files with their Claude instance. Soon, a bad actor is chatting with Claude to extract bank details or customer PII.

The most dangerous aspect of this attack is that Claude Cowork users are often non-technical. They routinely upload files that they find on the Internet. Some of these files are written by attackers.

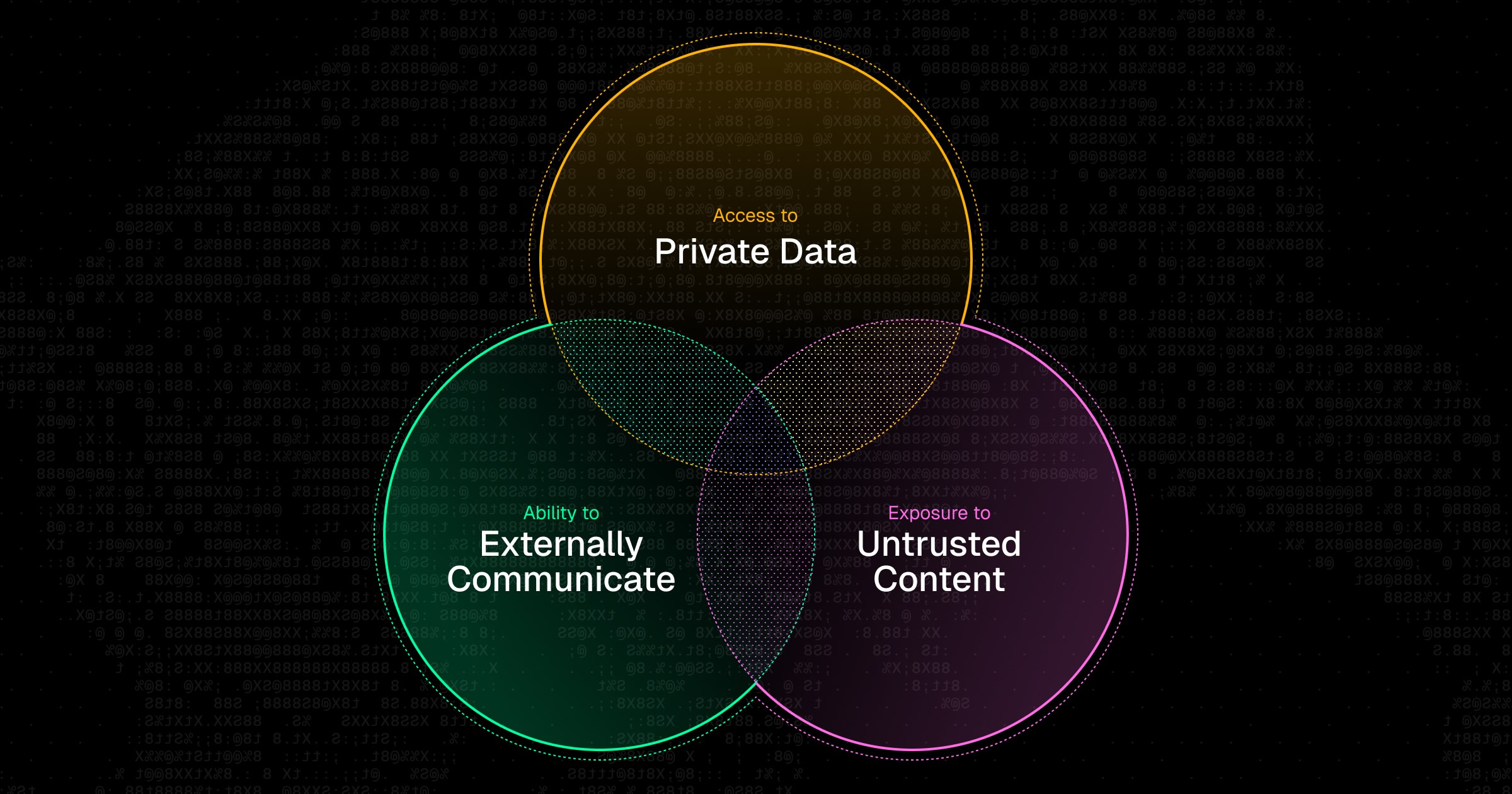

These attacks rely three shared tenets

Both attacks share three common tenets:

- It’s easy to trick users into clicking or uploading a resource that appears legitimate to the naked eye, but actually isn’t. When dispatched via spoofed emails or downloaded from innocuous websites, these resources can conceal their secret intent. AI agents trust authenticated users, so attackers just need to gain trust of any user.

- Copilot and Claude Cowork have thin guardrails that attackers bypass with clever instructions. For example, Copilot forbids exfiltrating plaintext sensitive data and Cowork refuses to execute arbitrary curl requests, but both platforms failed to apply these rules in edge cases.

- Users could be stolen from without ever realizing it. Both of these attacks don’t leave a noticeable trace as they rely on a single mistake, not an ongoing oversight.

Attackers are clever. They spend weeks engineering prompts that are designed to sidestep public, well-documented guardrails from model and agent providers.

Even the most security savvy individuals can be tricked by these attacks. They can easily trust assets that appear “legit enough”. Today’s exploits don’t live on sketchy websites with nonstop pop-up ads; they’re instead concealed on everyday websites, documents, and newsletters.

The only way to protect against these bad actors is with a security layer that aggressively thwarts attacks by being trained on the latest exploits and their respective variants.

Runlayer detected both of these attacks

Runlayer blocked both Reprompt and the Claude Cowork exploit—without any additional fine-tuning.

The product checks every input and output for industry-wide attack patterns. Unlike Copilot and Claude Cowork’s built-in safeguards, which make concessions in favor of streamlined UX, Runlayer is aggressive at identifying attacks by looking for the latest attack patterns.

Runlayer employs four strategies to keep our security analysis models up-to-date:

- Continuous Monitoring: We track security disclosures from industry researchers and threat intelligence sources, such as this week’s attacks from Varonis and PromptArmor.

- Rapid Response: When new attack patterns emerge, we generate diverse training examples and update our models quickly.

- Generalization Testing: We test against novel variants—not just disclosed examples—to ensure robust detection.

- Low False Positive Rate: Our testing includes benign examples to ensure legitimate tool calls aren’t blocked.

With Runlayer, you have that extra layer that prevents emerging threats from stealing your data or causing infrastructure damage to your systems. If you are interested in following today’s evolving exploits, track it on our security threat coverage tracker.